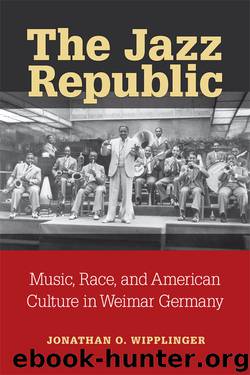

The Jazz Republic: Music, Race, and American Culture in Weimar Germany by Jonathan Wipplinger

Author:Jonathan Wipplinger

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Michigan Press

Published: 2018-05-15T00:00:00+00:00

Page 165 →

Chapter 6

Singing the Harlem Renaissance

Langston Hughes, Translation, and Diasporic Blues

The mood of the Blues is almost always despondency, but when they are sung, people laugh.

—Langston Hughes (1927)

In June 1932, “loaded down with bags, baggage, books, a typewriter, a victrola, and a big box of Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Duke Ellington and Ethel Waters records,” the African American modernist poet, jazz and blues fan Langston Hughes embarked from New York on a trip that eventually took him across the Soviet Union, Central Asia, and, for one, maybe two nights, to Berlin, Germany.1 Already widely recognized as one of the most important poets of the New Negro modernist movement also known as the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes set sail with a small group to film “Black and White,” a Soviet-financed depiction of racism in the United States. On this journey, Berlin and with it Weimar Germany were but temporary stops and his first experience of the German capital was not a particularly positive one. About this “wretched city,” he later commented: “The pathos and poverty of Berlin’s low-priced market in bodies depressed me. As a seaman I had been in many ports and had spent a year in Paris working on Rue Pigalle, but I had not seen anywhere people so desperate as these walkers of the night streets in Berlin.”2 Yet it was also in Berlin that Hughes came to experience the African American presence in Germany. At the Haus Vaterland’s Turkish café, Hughes observed a Black waiter pouring coffee, whom he describes as a “Blackamoor in baggy velvet trousers, gold embroidered jacket and a red fez.”3 Assuming him to be African, none in his group attempted to speak to this foreigner in a foreign land, but when the waiter heard the group speaking English, he burst out: “‘I’m sure Page 166 →glad to see some of my folks!’ [ . . . ]‘Say, what’s doing on Lenox Avenue?’”4 If Hughes relates no further information regarding who the waiter was or why he was in Germany, the presence of this Harlemite in Berlin can stand in for the current state of knowledge regarding the Weimar encounter with the Harlem Renaissance and its jazz poet laureate Langston Hughes: virtually unknown, often misrecognized, and yet there, waiting to speak.5

Indeed, the German translation of Langston Hughes began in 1922, at a time when Hughes was but 21 years old, long before he became a dominant figure of African American poetry, and it continued almost unabated until 1933. Translators of the period were particularly attracted to his work—all told, there were seventeen different translators of his poetry into German, who produced more than sixty individual translations of his work. To be sure, these are not evenly distributed, neither chronologically nor geographically—most were published between 1929 and 1931 and had at least some connection to the Austrian capital, Vienna. Still, the poems, their translators, and the various modalities, personal, textual, and political, by which German-speaking authors came to engage with his work have much to say to us.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13161)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11278)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7234)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(5914)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(5818)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5486)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(4831)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4573)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(3884)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3311)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3291)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(3119)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3083)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(2995)

How Music Works by David Byrne(2932)

Jam by Jam (epub)(2859)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(2777)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2687)

Petty: The Biography by Warren Zanes(2557)